Why should we abandon buildings once they no longer serve a purpose? A new book reveals the best projects: finding new uses for factories, grain silos, and market halls.

Here are 10 of the most ingenious—and inspiring—spaces around the world.

“The shifts in how we live and work have radically altered our cities,” writes Ruth Lang in the new Gestalten book Building for Change: The Architecture of Creative Reuse. “The spatial demands of working patterns have been utterly transformed over the past 50 years.” Many of our buildings could last for 50, or even 100, years; yet “fashion and changing patterns of use often curtail this lifespan, which sometimes barely stretches to a decade”. Instead of abandoning these structures, however, designers are developing innovative solutions that find value in the buildings that have been left behind, in place of our obsession with newness.

Building for Change explores how creative reuse could be the way forward for designing spaces around the world. While some architects are restoring and adapting existing buildings to meet new purposes, others are designing structures that can be readily repurposed for alternative uses in the future. As Lang writes, “innovation doesn’t always have to mean creating anew – it can mean approaching existing resources in new ways”. Even within those parameters, ambitiously creative designs are still possible – ones “that push the limits of architectural imagination”. Here, 10 projects – including former factories, sugar mills, grain silos and market halls – reveal the most ingenious, imaginative responses to an increasingly urgent global challenge.

Baoshan WTE Exhibition Centre, Shanghai, China

Kokaistudios

A former steel mill in Shanghai has been transformed into an eco-park that features a new thermoelectric waste-to-energy power plant, wetlands, an exhibition centre, and offices. One of the last remaining industrial structures in the city’s Luojing neighbourhood, the factory is a heritage site. Architects Kokaistudios kept the structure intact, fitting an independent modular system of panelling around the existing steel frame, “reimagining its rusting pipework and machinery as a design feature rather than a problem to be dealt with,” according to Building for Change. The polycarbonate screens are reusable and lightweight, which “enables the interior spaces to be flexible in configuration, reducing costs and construction times for adaptations as the site develops and the users’ needs change”. They also mean that the site’s appearance is transformed from ‘darkly overbearing’ to ‘warmly welcoming’ – even at night, when the building glows from within.

Kibera Hamlets School, Nairobi, Kenya

SelgasCano and Helloeverything

Just as the modular structure of Baoshan allows for dismantling and removal for future reuse on an alternative site, a project in Denmark embedded a second life into its initial design. “In accepting the commission to create a temporary pavilion for the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art near Copenhagen, Madrid studio SelgasCano and New York’s Helloeverything pre-empted an afterlife for their creation”, according to Building for Change. “They designed a structure that would not only suit the purposes of the brief, but which could be deconstructed, transported, and relocated elsewhere.” The former exhibition pavilion now houses a school for 600 pupils in Kibera, one of the largest urban slums in Africa. Dutch photographer Iwan Baan suggested the project’s new incarnation, which provides educational facilities for nursery, primary and secondary pupils in 12 enclosed classrooms. Utilising the universal modular scaffolding system, which can be easily transported and adapted, the structure was constructed over two months by the architects and 20 members of the Kibera neighbourhood.

Alila Yangshuo Hotel, Guangxi, China

Vector Architects

Surrounded by ancient villages in an ecologically protected setting, this abandoned 1960s sugar mill has been converted into a luxury hotel by Vector Architects. The landscape is as much a feature of the site as the buildings, and a structural truss – previously used for transferring sugar cane to boats on the Li River below – has been stripped back to its functional concrete core, which now frames a newly built pool. The original construction of the buildings has been largely retained and simplified, with one wing of the hotel serving as a sound barrier to the highway that runs alongside the site.

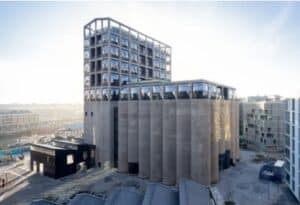

Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, Cape Town, South Africa

Heatherwick Studio

This 1920s grain silo on Cape Town’s Victoria & Alfred Waterfront was the tallest building in sub-Saharan Africa until the mid-1970s – and has been decommissioned since 1990. “The agricultural structure is an emblem of South Africa’s colonial history as well as another chapter in its post-Apartheid future,” according to Building for Change. “Its transformation fractures these historic associations without denying them, to form what… is renowned as the world’s largest museum dedicated to contemporary African and diaspora art.” London’s Heatherwick Studio carved into eight of the 42 reinforced concrete tubes that made up the grain lift and storage annex, to form 80 galleries across six levels, as well as a massive void at the centre “within which the nature and complexity of these spaces can finally be appreciated”.

Kamikatsu Zero Waste Centre, Kamikatsu, Japan

Hiroshi Nakamura & NAP

“In 2003, after the forced decommissioning of its waste incinerator, the municipality issued a Zero Waste Declaration requiring all waste produced by the area’s residents to be reused or recycled to reduce the demands for landfill or incineration,” according to Building for Change. “Rather than increase emissions by shipping waste to the nearest city for processing, a new centre was created, where residents can separate and source materials for recycling and reuse.” To challenge public perceptions of a “waste centre”, the site includes a shop selling reclaimed items, a community hall, a laundry, a hotel and an educational space for research into ways of increasing reuse. The horseshoe-shaped plan allows easy access to materials, while the center’s construction incorporates waste materials from local houses, schools, and government buildings left derelict by the area’s depopulation— including 700 retrieved windows that form the walls of the structure, bolstered by plastic crates once used for mushroom harvesting. Local residents now recycle 80% of their waste, compared to a national average of 20%.

Qinglongwu Capsule Hotel and Library, Jinhua, China

Atelier tao+c

The 20 capsule bedrooms in this former barn are surrounded by bookcases made from locally-sourced bamboo, while the bathrooms sit in the roof space. Architects Atelier Tao+C staggered the bedrooms throughout the building, interspersed with double-height spaces, which added to the sense of lightness created by the suspended framework. The self-contained construction is separate from the building’s skin, and in places, the steel grid is concealed within the bookcases, which provides a sense of privacy.

EOI Melilla Language School, Melilla, Spain

Ángel Verdasco Arquitectos

One of two autonomous Spanish cities located in North Africa, Melilla borders Morocco. When its central market building closed in 2003, it “created a rupture in the neighborhood’s cohesion,” according to Building for Change, as the 90-year-old commercial centre was a “social catalyst” connecting the city’s Christian, Muslim, and Jewish communities. Ángel Verdasco Arquitectos won a 2008 competition seeking a design that embodied the market’s social value, with their proposal transforming the site into a music academy, a language school, and an educational centre for adults— providing “cross-cultural connectivity” that offers Melilla’s different communities a place to interact. The original market walls were left freestanding, enclosing the structures within and building upon “the memories and identity of the market, which might otherwise have been swept away”. An aluminium lattice frame is a contemporary reinterpretation of local Islamic architecture, mirroring perforated jail screens that control light and ventilation through an interior space.

Inside, the derelict market hall has been stripped back to its skin, within which a new structure that echoes the social purpose of the historic building has been constructed, according to Building for Change. “The centre acts as a mediating space for the different communities and functions that occupy the site,” and fosters multiculturalism by reappropriating the market structure for its new purpose.

Castle Acre Water Tower, Norfolk, UK

Tonkin Liu

“Built in 1952, this water tower in Norfolk, England, wasn’t originally deemed worthy of saving by local authorities,” according to Building for Change. Once situated on an airfield, local authorities auctioned it as scrap. Fortunately, new owners rescued it and transformed the tower into their home. By cutting a ribbon window, and replacing one line of the panelled steel grid that forms the walls of the tank, the architects produced panoramic views of the surrounding landscape.

A timber stair enclosure braces the tower, preventing the roof from shifting against the lower level in high winds, while a stair tower acts as a thermal chimney, creating ventilation when the windows are closed. Waste materials were reused, with the unit clad in recycled aluminium-plastic panels, and the stair tower’s balustrade was made from steel tie rods that were removed from the tank.

Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and Arts, Hong Kong

Herzog & de Meuron

“Built as a compound by the British after taking control of Hong Kong in 1841, the Central Police Station, Central Magistracy and Victoria Prison have all since been listed. Along with 16 other historic buildings, they occupy… ‘the largest heritage conservation project in Hong Kong'”, according to Building for Change. The buildings were so old that they had no construction records, meaning engineers needed to conduct a forensic investigation to plan an appropriate method of repair. There were other challenges when creating the two new structures: minimising vibration during works to avoid damaging existing buildings and using innovative methods of creating foundations due to the high density of the site, which is now a cultural and shopping centre.

Lakeside Plugin Tower, Beijing, China

People’s Architecture Office

A prototype demonstrating the benefits of modular construction, located in an area of protected farmland, Lakeside Plugin Tower is intended to touch the ground lightly, minimising disruption to the ecology, water table and wildlife of the site, and enabling easy removal to other sites in the future. “The modules are designed for easy transport from the factory, where they are prefabricated and can be assembled without skilled labourers,” according to Building for Change. A large variety of shapes and potential configurations allows for a more creative assembly, enabling users to angle units to take advantage of views and create different combinations of textures and colours with the panels. That changes the role of the architect, who relinquishes control over layout, shape, size, and colour. It also extends the building’s lifespan almost indefinitely. “The house’s plug-in structure is designed to be added to and adapted over time, as shifts in technology and the needs of its occupants dictate.”