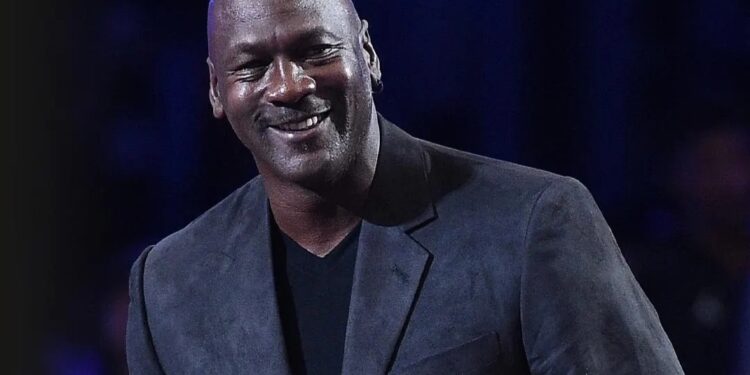

Since Michael Jordan stepped onto an NBA court for the first time in 1984, earning an outsized payday has been a layup, Forbes reports.

Across his 15 NBA seasons, he hauled in $94 million and was the league’s highest-paid player in 1997 and 1998. But it was off the court where Jordan put serious air between himself and every other athlete on the planet, earning an estimated $2.4 billion (pre-tax) over his career with brands such as McDonald’s, Gatorade, Hanes, and, of course, Nike, where his most recent yearly royalty check was for some $260 million.

Jordan had his biggest score in August, though, when he sold his majority stake in the Charlotte Hornets at an eye-watering $3 billion valuation. Even if he had sold at Forbes’ most recent valuation, an estimated $1.7 billion in 2022, it would have been a coup for the 60-year-old Hall of Famer. Instead, the 27th most valuable franchise in the NBA traded hands for the second-highest sale price in league history and nearly 17 times its value when Jordan became its principal owner in 2010.

That places him in rare air. With an estimated net worth of $3 billion, Jordan has arrived on the Forbes 400, marking the first time a professional athlete has ranked among America’s wealthiest individuals.

“Michael’s one of the few people that have had success three times,” says Ted Leonsis, the Washington Wizards, Mystics, and Capitals owner, who has partnered with Jordan on multiple investments and sports ownership in the past. “A lot of entrepreneurs make it once. They have a big win, take their winnings, retire, and [we] never hear from them again, or they try something a second time and it doesn’t work. He’s had three mega successes,” referring to Jordan’s impact as a player and an owner, as well as the growth of the Air Jordan brand at Nike.

The prospect of a professional athlete becoming a billionaire is still highly irregular; only three individuals have ever done it. Jordan was the first to achieve that milestone in 2014, and LeBron James and Tiger Woods have since followed, doing so while their careers are still active. With sports salaries skyrocketing and off-the-field opportunities growing, more are surely to follow, as evidenced by the fact that seven athletes, by Forbes’ count, have already notched $1 billion in career earnings before taxes, spending, and agents’ fees.

Still, joining the three-comma club requires a perfect storm of favourable circumstances. Or, as Mark Cuban, the billionaire owner of the Dallas Mavericks, puts it, “[athletes] need to get really lucky.” But that seems hardly the case for Jordan, who had success as soon as he entered the NBA.

When the first Air Jordan sneaker was released during the tail end of his rookie season in 1985, Nike reportedly expected to sell $3 million worth of merchandise. Two months later, the brand had $70 million in sales and $100 million by the end of the year, according to a 2023 study from Temple University. Jordan had signed on for five years initially, earning $500,000 annually plus royalties. In its latest annual report, Nike reported $6.6 billion in annual wholesale revenue for the Jordan Brand, up 28.6% from the year prior.

Nike wasn’t the only company trying to capitalize on Jordan’s talent and charisma. “He was a brand before people discussed human beings being brands,” says Marc Ganis, president of the consulting firm Sportscorp. “It wasn’t Michael Jordan promoting Gatorade; it was Gatorade saying, ‘Drink Gatorade to be more like Michael.’”

But shortly after his second retirement from the NBA in 1998, Jordan started to transition away from life as a celebrity pitchman. According to ESPN, he made unsuccessful bids to buy the Hornets (which later became the New Orleans Pelicans) and the Milwaukee Bucks. Jordan eventually joined a Leonsis-led ownership group that bought the NHL’s Washington Capitals and 44% of the Washington Wizards, and he assumed the role of president of basketball operations under the latter’s then-majority owner, Abe Pollin.

“He was a sponge,” says Leonsis, who recalls Jordan being very curious and asking lots of questions. From selling sponsorships to advertisements, Leonsis imparted what he knew about the business of sports. “Ultimately, he was more right than I was, which was that if you have a great team and you have star players, it’s easy to sell tickets, suites, and sponsorships.”

Jordan’s two-season return to the court meant divesting his ownership stake, and when he retired for a third and final time in 2003, he didn’t wait too long to buy another team. Jordan purchased a minority stake in the Charlotte Bobcats in 2006 and, four years later, became the NBA’s first player-turned-majority-owner in a deal mostly funded by debt that valued the franchise at $175 million, a considerable drop from the initial $300 million BET founder Robert L. Johnson paid for the expansion team in 2003.

Despite his ultra-competitive nature, success on the court never followed for Jordan’s Hornets (the team dropped the Bobcats moniker in 2014), losing in the first round of the NBA playoffs three times in the past 13 years. That didn’t stop Jordan from riding a wave of rapidly appreciating sports franchises. In 2019, he sold 20% to Melvin Capital founder Gabe Plotkin and D1 Capital Partners founder Daniel Sundheim at a $1.5 billion valuation. The team eventually sold for double that price when Jordan ceded majority control to Plotkin and another hedge fund founder, Rick Schnall, two months ago. As far as NBA teams go, only the Phoenix Suns have sold for more—when United Wholesale Mortgage CEO Mat Ishbia bought the franchise at a $4 billion valuation earlier this year.

“Now people go, ‘Well, if Charlotte sold for X, and I’m in a bigger market and I do more revenue, that must mean my team is worth Y,’” Leonsis says. “He did a really great deal, and it helps everybody. If he had done a fire sale deal, then people wouldn’t be happy with him.”

Jordan retained a small stake in the Hornets, which will keep him connected to basketball while he searches for his next business venture. Over the years, Jordan has dabbled in other businesses, including car dealerships, restaurants, a premium tequila brand, and, more recently, equity investments. He’s bought into CLEAR, Mythical Games, and Dapper Labs, to name a few, as well as DraftKings and Sportradar, both of which came through Leonsis.

For Jordan’s next challenge, Leonsis expects NASCAR to occupy a larger place in his business life. In 2020, Jordan cofounded Cup Series team 23XI Racing with Joe Gibbs Racing driver Denny Hamlin. “I bet you it’s going to end up being a great business for him too,” Leonsis says. “It’s his competitiveness and desire to win.”