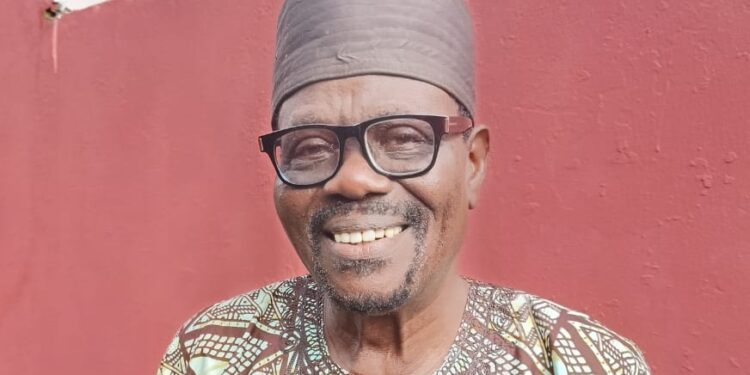

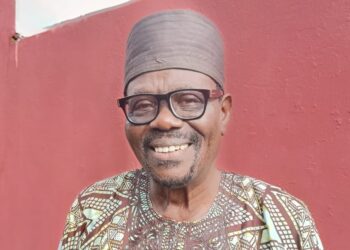

Akogun Tola Adeniyi, Chairman/Managing Consultant of The Knowledge Plaza—a body of ghostwriters, speechwriters, biographers, and editorial consultants—was Chairman/Editor-in-Chief of the old Daily Times Conglomerate, a former Permanent Secretary in the Presidency, a former acting Editor-in-Chief of the Nigerian Tribune, and a former Deputy MD/Managing Editor of the defunct Sketch newspapers.

Adeniyi, Africa’s first newspaper ombudsman, has held senior editorial positions in the Lancashire Evening Post, Burnley Express, and Atlanta Enquirer in the UK and the Atlanta Enquirer in the US. He was also a visiting lecturer (Theatre & English) at Lancaster University, UK.

He was born on May 29, 1945.

In this interview with REPORTERS AT LARGE, Akogun Tola Adeniyi, who clocks 80 years today, bared his mind on his life experiences, leadership and decision-making, and historical context and perspective about politics and society. Excerpts:

Life experiences

Some of the most significant events or challenges faced in career and public life:

I don’t know about challenges. I didn’t have any challenges. Not in my life itself. No, no, no. But my career, I say career… My career may begin with being the official reporter at Sagono School. I had a notice board called the Writers Club on which I posted articles criticising and fighting everybody. Then, of course, I faced the challenge of envy from my contemporaries.

I was the Editor-in-Chief of Ago-Iwoye Secondary School’s magazine, The Spartan, and the Ijebu Muslim College, Ijebu-Ode, The Scientia. Overall, I didn’t face any major challenges.

I faced no challenges as a bookseller, University of Ife bookshop manager, information officer, cultural officer, or education officer. Within three months of joining the Daily Times, they made me the Regional Editor of Ibadan. That opened the world because that was where I built all my early contacts. I interviewed who-was-who in Ibadan and the Western Region because my portfolio covered the entire Western Region.

Again, I don’t know about challenges. I capture this in my autobiography, “Life Scripted by Destiny and Acted by Fate.” So, my life trajectory had always been in the hands of God and destiny. I was born, and I just started queuing into the script written by Olodumare. If Olodumare wrote something, that thing could not say it faced any challenge because Olodumare had scripted my life: this is where you are going, and it went like that. Up till now, there might be some distractions here and there. There could be envy, bad-mouthing, and other things, but not the challenges people usually face. I’m not saying it’s been running smoothly or totally smoothly. Still, I had no huge challenges, as others might say they had them.

I remember in those days, my father had some spiritual guardians, especially being a devout Muslim. I finished the Quran, and I graduated from primary school at the age of 10. And about that time, the Parakoyi in Ago-Iwoye, whom we believed was the greatest seer of his time, would tell you what would happen to you in 50 years and said, in my presence, “He would be a famous and celebrated world journalist; he would live abroad and employ whites.” If you had such a thing drummed into your ears at that age, you are likely to begin to imagine that it would come into reality. And I had all my father’s and mother’s support and encouragement. Even the things I lacked were provided by other entities because we didn’t have many silver spoons. So, I was okay.

I came to the notice of the Ago-Iwoye community and council, and they gave me a bursary. I was a scholar from secondary school. The Ago-Iwoye community and the Ago-Iwoye council paid my tuition fees throughout my secondary school education. At 14, I was an Akewi on Radio Nigeria, earning some money. At 16, I published my first book, Aye Ode Oni, which I sold in all the Nigerian colleges. I also made money from that. In high school, I occasionally collected firewood to sell because there was huge construction work at the Muslim College. In essence, I didn’t lack as such. When my parents could not meet the financial burden of financial challenges, Olodumare gifted me enough energy and resources to make money.

So, by the time I was in high school, I was paying the school fees of my immediate younger sister and the one next to her. I had no problem attending university because I had Western Region and Federal Government scholarships. But as you started entering the world, there would be competitors and competitions. There would be people who would not like you, not for any reason other than envy. There would be people who would not want your guts. So those could give one an emotional challenge that you bother about them. Anybody who is given a taste of malice will likely feel it.

But specifically, I wouldn’t have faced any major challenge.

When I started my company after leaving the Nigerian Tribune in anger in December 1980, I went full blast into my organisation, Deto-Deni Publishers (incorporated in 1974). Now, I have Canada University Press in Toronto, incorporated in 2000. So, it was challenging to provide sufficient capital for the company. I had a restaurant, a guest house, a bookshop, a commercial press, newspapers, Sunday Stamp, edited by Femi Odugbose, and Naked World. I also established a technical college, the Apostolic Institute, in Deto-Deni Publishers. So then, I had some sleepless nights and faced challenges in my career as an entrepreneur. But the moment I made Public Relations the most significant part of my business, I started breaking even. I was the reputation manager and chairman of the Oyo State Institute of Public Relations for two terms. I was laundering people’s images. I also went into ghostwriting, writing people’s books and then putting their names on them. I also went into the real estate business and built a block of eight flats on Ring Road, this one, and so on.

However, all these properties were put up for auction at one point. They wanted to sell this place. It was published in Sketch and Tribune, and an auction notice was even put on the door at my place on Ring Road. The only one they didn’t put up for auction was the one in Ago-Iwoye. But again, it was a storm that dissolved. So if you are discussing challenges, I still return to the words. I didn’t have, honest to God, significant challenges. I’ve been lucky all my life.

Some of his most significant life events

Again, the most important thing in my life was responding to destiny. I have been a public man: a writer, an actor, a distinguished actor in my days at the University of Ibadan. I wrote and produced plays at HSC, my secondary school, and even my primary school. I was President of Cultural Arts at Muslim College, President of Cultural Arts at the University of Ibadan, President of the Drama Club, President of the Literature and Race Society, and President of all West African universities’ Literature and Race Societies.

So if you had that kind of exposure, you were likely to have a lot of women running after you, or you were running after them. So I had that. But when it was time for me to get married, I met a night guard at a plank market who said, “Don’t worry, the woman you will marry will come to your house. You don’t have to look up; don’t look for any woman; the woman you will marry will come to your house.”

But in late August 1972, on my way to Abeokuta, I met an old friend, Remo de Wokobia, who asked, ‘Where are you going?’ I said, ‘I’m coming to your place in Abeokuta.’ Then, we went back to Abeokuta. When I came back, he was at a birthday party for a one-year-old child. It was an awkward place where you would meet a graduate teacher. But one of my wife’s father’s tenants was also a teacher in the school where the woman taught. So she asked my wife to accompany her to the party. And being a weekend, she taught at the Muslim College in Bode as a graduate teacher. When I got to that party, she was there, sitting down. I just went to join them. Then I said to her, ‘Your face is familiar.’ She said, ‘Yours is familiar, too.’ Then she said, ‘You are an actor.’ And I said, ‘Yes.’ At that time, she wasn’t the kind of woman I would ever go to propose to. Certainly not. Beautiful girl, you know. So when they were about to go, I offered to take her home. Again, this is where fate meets destiny.

I took her to her house in the Salvation Army. Then, I said, ‘Can I meet your mom?’ So I just went upstairs to meet the mother in the kitchen. Then I saw an almanack hung on the wall. This was August 23 or August 24. I looked at the Almanack and saw that December 2nd was a Saturday. This was August 23. I told the woman, I said, “Mama, I’m coming to marry your daughter on December 2nd.” That was audacious. And it happened. On December 2nd, we got married. So it was a significant moment in my life.

During the short courtship, I visited her on the weekend. Then, I met a man there. The driver had white gloves. So I said, ‘This big man had come to see this woman.’ So I was very angry with myself. I couldn’t say so. I had already fallen in love with her. And I met this gentleman there. With a posh car, with a driver in uniform. So I couldn’t stomach it. I stormed out of the house, saying, ‘So a man is coming to see her.’ I didn’t realise then that the man was a junior friend of the father’s. He was the editor of a paper. The father was a senior principal education officer overseeing the ministry’s publications. So they had something to link them together. Then the man was also her teacher in Oyo, where she had her HSC.

So I got angry. I went downstairs. But as fate would have it, my car refused to start as usual. Then there was drizzle. And I thought it was going to rain. So the gentleman had now finished his visit. He still met me downstairs, battling with my car. And he said, ‘Young man, where are you going?’ I said, ‘I’m going to Polytechnic Road.’ He was going to the Ring Road but offered to give me a ride. So, I swallowed my pride and got a lift from someone I thought was a rival. What was going on in my mind? If I had a dagger, I would have…

As I was going inside, I told him I was the manager of a bookshop and that, at that time, I was already a columnist in Sketch and a magazine in Afriscope. And, of course, I had just resigned from the Ministry of Information. So I was the Chief Press Officer and so on for the government.

Then he introduced himself as Editor of the Daily Times. I said, ‘Wow! My application is sitting down there.’ After talking to me for less than two kilometres, he said, ‘You’re a very sharp boy.’ By Tuesday, I had an invitation to come to Daily Times. And that changed my life forever. Since then, I haven’t jumped from company to company. It was the same journalism I had been doing since 1972.

And as Ogundele mentioned in one of his tributes to me, “While all of them were struggling to be this, to be that,” he said, “Tola distinguished himself so remarkably.” In the history of that paper, to be made Regional Editor after three months was a record. At that time, they employed some teachers from the University of Lagos. Aruna Adamu was there.

In less than three months, I fed the newspapers with articles in Lagos. Josse said, ‘Go and head the Daily Times in Ibadan.’ Of course, somebody was in the bookshop; I was only known by colleagues in the university and those in the drama or acting fields, but not to the public.

So, coming to Ibadan in March 1973, I interviewed the head of the police, the head of the army, the head of the civil service, the head of the water corporation, the head of the service, the secretary of government, and the head of the military… It was very important because, at that time, the Daily Times was selling about 700 to 800,000 per day, close to a million. So whoever was working with that kind of newspaper… —if they had not seen a reporter from the Daily Times at any public function in the Western Region, they would not start.

In less than three months of arriving in Ibadan, I was all over the place. I was sending about two or three interviews to the head office weekly. Then, I had already started the ‘Economy’ column in the Sunday Times. The significance is getting into the Daily Times and making a career of that opportunity. It was the most significant part of my life.

And of course, the marriage that followed it. I was married on December 2nd, 1972. By March 73, I had got a brand new car. Before August, I had taken my wife out of teaching to join the civil service. The Daily Times gave us one of the most prestigious houses imaginable. Chief Onagoruwa, the General Manager of Cooperative Bank, owned that house at the junction of Liberty Stadium Road, which was a beautiful home. All I’m saying is that I had become a celebrity between December 2nd 1973, and June of 1974. I had, and then my fortunes just quadrupled. My wife was in the civil service. We had our first baby. Everything was smooth sailing. That period was very, very significant in my life. And it has remained ever since because many other fortunes followed.

The pinnacle of a journalism career was to be the chairman and editor-in-chief of the Nigerian Tribune and the Daily Times. I’m the only person who ever combined those two positions—the chairman of the board and managing director was Babatunde Josse. I was the second to occupy that position. Those positions are the last to occupy such a position. It’s also significant to be the chairman of the Daily Times. And I was also appointed the paper’s first sole editor before becoming MD.

Being a permanent secretary was significant in the sense of the assignment given to me. When I was appointed permanent secretary, I coordinated the movement of Nigeria’s capital from Lagos to Abuja, including all the government agencies, ministries, etc. That was also a very, very significant position. I was the one who gave the key to Abuja City to Babangida on December 12, 1991. So, those are significant moments in my life.

Several other things happened when my first daughter married and later qualified as a medical doctor, and when I moved to my first house on Ring Road in 78 or 79. Then, my first chieftaincy in Ago-Iwoye was as the Bobagunwa of Ago-Iwoye in 1981. The Alaafin of Oyo came to commission my home there. Only the governor of Bendel, Ali, could not come. So when I had an event, as young as I was, the Alaafin was in attendance. He came with 11 buses. We had the Governor Olabisi Onabanjo, and so forth. I was in my 30s, you know. That was also significant.

My journey has been a testament to the power of passion and perseverance. From my early days as a young achiever on Radio Nigeria to my pivotal turning point at the Daily Times, I’ve been blessed with opportunities that have shaped me into the journalist I am today. I’m humbled by the gift of writing that Olodumare has endowed me with, and I take pride in being a writer at heart. My friends and classmates from the University of Ibadan often say that if I had remained in academia, I would have become a professor by my late 20s, given my prolific writing—16 columns a week—a feat few columnists worldwide could match. This legacy of productivity and dedication is a reminder that with hard work and divine favour, the possibilities are endless.”

Akogun Tola Adeniyi: How upbringing and background shape his values and decisions

My father’s wisdom has been a guiding light in my life, shaping my values and philosophy. One particular lesson he taught me at maybe 11, 12, or 13 has stayed with me today—a testament to his foresight and concern for my well-being. He’d often take me aside, under the cover of darkness, and impart words of wisdom that would stay with me forever. His words were a shield, protecting me from the uncertainties of life.

He’d say, “Life is precious, and safety is paramount. Never compromise your integrity or put yourself in harm’s way for fleeting pleasures.” This lesson has been a cornerstone of my journey, reminding me to prioritise my values and make choices that honour my principles. Today, I carry this wisdom with me, and it’s a reminder that the lessons we learn from our loved ones can profoundly shape our lives’ trajectory.”

He would say, “It’s death. Don’t ever sleep in a woman’s house. Never. If you go and sleep in a woman’s house, maybe the woman quarrelled with her husband or boyfriend, but you don’t know whether they’ve made up. If there was an armed robbery or anything happened, and you got entangled and you were killed, what do you tell God? It’s not safe. You could be in a woman’s house, too. But don’t sleep there. It’s not safe,” And I kept that till today.

Then my father would tell you, always saying, “There’s nothing anywhere. There’s nothing anywhere.” He would say that every day. So don’t attach too much importance to anything. Don’t carry the world on your head. You are just another person.

So, in those days, even when I got older, if my father was talking to me and I was getting in a hurry and I was looking at my wristwatch, my father would say, “Where are you going? I’m talking to you, and you are looking at your wristwatch. Are you going? Are you going? So why are you? Why?” So he taught us the virtue and value of patience, respect for the other person, humility, kindness, and honesty.

“My upbringing was profoundly shaped by my parents, who instilled invaluable virtues and values that guided my personal and professional journey. My father, a stalwart leader, served as treasurer of the Ago-Iwoye Muslim Community for an unprecedented 50 years, demonstrating unwavering dedication and integrity. His fearlessness, kindness, and commitment to family and community have been a constant source of inspiration. My mother, with her boundless love, care, and selflessness, taught us the importance of empathy, compassion, and sacrifice. Their influence has shaped my worldview, emphasising the need to be kind, respectful, and considerate towards others, particularly those less fortunate.

Their example of hard work and industriousness has also had a lasting impact on me. My father’s entrepreneurial spirit, evident in his travels across the country for business, and my mother’s tireless efforts in caring for our family have instilled a strong work ethic in me. These values have enabled me to maintain a prolific writing schedule, producing 16 columns a week while conducting interviews and engaging with diverse individuals.

I’m grateful for the lessons I’ve learnt from my parents, which have shaped my approach to life and work. Their legacy inspires me, and I strive to emulate their virtues.

Essential guiding principles for effective leadership

Integrity, integrity, integrity. Any leader must be trustworthy, have integrity, and embody the ethos of what Yoruba call Omoluabi.

Yoruba has a value system: the first is integrity, the second is wisdom, knowledge, and understanding (the application of the three is essential), the third is valour, then visible means of livelihood, and the fifth is money.

For effective leadership, you must have the five values; even if you don’t have the fifth one, you must have the remaining four.

A difficult decision was made…

One of the most challenging decisions I’ve made was letting go of my immediate younger sister from her role as the Manager at my restaurant and motel. Despite our close bond, I realised that her actions were impacting the business and team morale. It was a tough call, but I knew I had to prioritise the integrity and success of my organisation.

I took a thoughtful and compassionate approach, securing a new job for her before deciding to part ways. This experience taught me a valuable lesson about the importance of separating family ties from professional decisions. I’ve since learnt that employing relatives can create conflicts of interest and make it harder to maintain accountability.

This experience has shaped my approach to leadership and business, reminding me that tough decisions can ultimately lead to growth and better outcomes. I’ve carried this lesson forward, applying it to future decisions and striving to lead with fairness, integrity, and wisdom.”

Then, when I decided to leave Nigeria to relocate to Britain and then to Canada, it was difficult for me because I had established strong roots and strong contacts and connections in Nigeria. I was already 50 years of age, and then to go and start living in another country, I didn’t find it an easy decision to make. Like I always joked when I went to Canada some 30 years ago, I would say I came from a place where I had access to every door. But I’m now living in a country where I don’t even have access to a window. But that is life. Those were decisions.

The choice to relocate abroad

Series of events… Late General Sani Abacha detained me: I had a very peculiar, complicated relationship and circumstance. I was very close to the late MKO Abiola, Babangida and Abacha. Abiola was humiliated and ridiculed by the system. You had Abacha taking over. I was writing Abacha’s biography. I was close to Chief Olusegun Obasanjo, and Obasanjo and Fela were sworn enemies. Abiola and Fela were sworn enemies. But I had no ill feelings against anybody. It was a challenging situation for me. When Abacha eventually took over the government, which I knew he would do anyway, I became uncomfortable because Abacha didn’t fully trust me again. I’m a Yoruba man. Blood is thicker than water. When Abiola turned 55, Abacha sent a military officer to me to plead with Abiola to give him an invitation card to attend that party. And that man later detained Abiola for four and a half years.

Abacha believed I was behind the newspaper publications against him, so I was arrested there. When they came here in January 1994, they ransacked my garage and every room in this house. I was arrested the same night that Beko and Yar’Adua were arrested. The three of us were charged the same night. It was the front page of the Concord, with the title “Abacha shows his fangs.”

So when I was arrested, they took me to some print houses to check whether I was printing some dirty magazines and newspapers. They said maybe Akilu and Olurin were hiding in my house, and perhaps I might be planning a coup. We did have some meetings, not with Olulun and Akilu, but some other groups were planning, if possible, to prevent Abacha from taking over power, or, as soon as he took power, how could we get rid of him so Abiola could be given his mandate.

Military people are very sensitive. To them, loyalty must not be 100 per cent. So he probably would think that if I were to hold any loyalty at all, it would be towards Abiola, not him, and not Babangida.

Anyway, after my detention, I was taken to the SSS and then kept underground there, sent to Abuja, and released. Anyway, I got out and found myself living in the UK and teaching at the University of Lancaster as a part-time lecturer and a guest lecturer.

The decision to leave Nigeria for Canada?

Before then, I’d sent my daughter out of the University of Lagos and my first son out of the University of Ife to the University of Leeds in the UK, even before I decided to go, because I didn’t believe I could ever live abroad. When I was chairman of the Daily Times, even teaching and studying for my master’s in Lancaster, it would have been easy if I had wanted to take British citizenship. I even told my children if I’m unfortunate to die in Canada, they must make sure, if it’s going to cost them a fortune, they bring my corpse here and throw me into the grave in Ibadan here. And they don’t need to come. I don’t want any of my children to come if I die in Nigeria.

However, it was a difficult decision when I felt unsafe remaining in Nigeria. I also knew how the military operated. I knew that military people are very security-conscious. Once they think that you could threaten them, they eliminate you. They don’t take captives. They just kill. And I felt that it was not safe.

It was a difficult decision. After all, I really would not have imagined I could live with the oyinbos because I have been Afrocentric. I believe that white people did a lot of damage to the Black race, so I shouldn’t find myself living in their midst. But I spent 30 years there.

How have Nigeria, Nigerian politics and society changed?

I don’t believe in Nigeria anymore. So, anything to do with Nigeria is out of my orbit. I don’t feel the country is going to survive. I think it’s going to die; it’s going to die a natural death. No nation on earth that runs the way Nigeria is run can survive. And I feel particularly saddened by what the children these days have been subjected to; I feel sad that they’ve ruined them. My generation was also responsible. They’ve ruined the future of the young people in this country. And nothing makes me sadder than that realisation.

And to crown it all, we don’t have political parties anymore. We don’t have men of integrity anymore. We have traders, businessmen, and contractors who hijacked power through thuggery and criminality.

We also have a citizenry that is so idiotic and imbecilic. I cannot imagine that somebody who has ruined your life will still be saying, “rankadede to them.” The way Nigerians worship politicians beats my imagination. I don’t know why the media men and the general public should hail them. They are just businessmen going from one company to another.

Like I said, everywhere, any idiot can be governor, any idiot can be minister, any idiot can be… But no idiot can be the MD of a newspaper office, a professor, or a surgeon. Therefore, surgeons, professors, media entrepreneurs, and editors should see themselves as superior to these rascals. And until they change that mindset, until they recognise and realise that they are superior to these charlatans, the country they call Nigeria and the citizens of this country will never know peace. They will never progress.

When you worship people who take you for a ride and who don’t recognise that you exist… Nigeria is a place where somebody with 1.3 billion thefts hanging on his neck holds a critical position in government.

So, to me, the solution would be returning to where we were before the Oyinbo man came. Let Yoruba be a Yoruba country. If you run a monarchy, let’s run a good monarchy. If you will run a theocracy, let’s run a beautiful theocracy. But not this kakistocracy, a government of idiotic, incompetent people. Or this bogus aristocracy, I mean plutocracy, a government of just the rich people. That’s all.