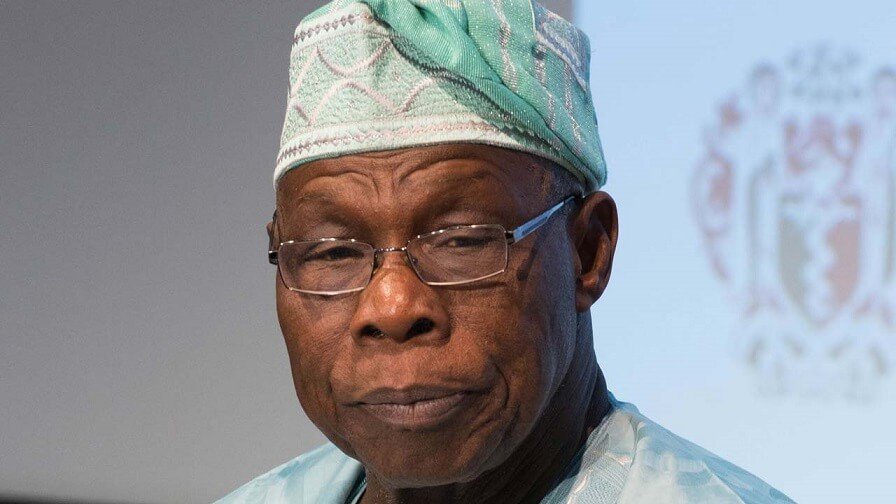

Former President Olusegun Obasanjo has always had strong opinions about Nigeria’s oil sector, and none stronger than his damning verdict on the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited (NNPCL). He has called it “a basket case” and “a den of monumental corruption.”

Coming from someone who once presided over NNPCL as Minister of Petroleum during his presidency (1999–2007), his words carry weight—and, perhaps, more than a little irony. Convinced that the oil company is a monumental failure, he was sold off the NNPCL during his presidency. However, his immediate successor, the late President Umaru Musa Yar’ Adua, reversed the decision and returned the company to its former status, a government-owned entity.

Obasanjo’s criticism of the NNPCL is blunt: he believes the company is structurally incapable of reform. Speaking in 2022, he declared that NNPCL is still not a commercial entity, despite the 2021 Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) that rebranded it. In his view, it is simply old wine in a new bottle—deeply politicised, inefficient, and opaque.

When Obasanjo went to town, declaring that the NNPCL is a drainpipe that can never work, many Nigerians, especially during the incumbent President Bola Tinubu administration, called him several unprintable names. Many outrightly called him a self-praising and self-appointed critic who sees nothing good in any of his successors ever since he left office in 2007.

Yet, as valid as his critique is, Obasanjo’s own record on the NNPC (as it then was) is complex.

During his presidency, Obasanjo doubled as Minister of Petroleum—a controversial move that gave him direct control of oil revenues. While some viewed this as an attempt to rein in corruption, others saw it as centralising too much power. Critics argue that under his watch, billions of dollars in oil revenue were not properly accounted for. The Senate once raised questions over $2.5 billion in unremitted funds. Also, the NNPCL remained opaque, with oil block allocations and contract awards shrouded in secrecy.

However, to Obasanjo’s credit, he attempted some reforms. He invited international oil companies to invest in deep offshore fields under new fiscal regimes. He also initiated some of the early steps toward deregulating the downstream sector.

Obasanjo’s administration also set the foundation for the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI), which was established in 2004 to bring transparency to the oil and gas sector. These were genuine, if limited, efforts to clean up the system.

But his failure to unbundle or restructure the NNPCL when he had maximum political capital speaks volumes. He may have lacked the will to take on entrenched interests, or perhaps the institutional resistance was too strong. Either way, he left office with the same NNPCL he inherited: bloated, inefficient, and riddled with leaks.

Today, Obasanjo speaks with the authority of a statesman, and in many respects, he is right. The rebranded NNPCL still operates with troubling opacity. It continues to fail in remitting oil revenues fully to the Federation Account, and it has become more powerful than ever—now posing as a “commercial” entity, while clinging to its old habits of secrecy and patronage.

But the words of Obasanjo also ring with the tone of one who had a chance to fix the system and did not go far enough. His insights are valuable—but they should also remind us that the rot in NNPCL did not begin today. It has been fertilized by years of institutional decay, presidential neglect, and elite complicity.

Obasanjo is not wrong when he calls NNPCL a monster. But he is part of the story of how that monster grew so large. That said, his warning should not be dismissed.

If Nigeria truly wants to break free from the oil curse, the NNPCL must be dismantled or transformed into a truly independent, accountable, and competitive player in the energy market—not a political cash cow.

NNPCL: Nigeria’s Black Hole Of Corruption And Missed Opportunities

Few institutions embody the tragic paradox of Nigeria’s oil wealth like the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited (NNPCL). What should be the engine of national prosperity has instead become a symbol of dysfunction, secrecy, and corruption. The NNPCL, formerly the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC), was ostensibly commercialised in 2021 under the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) to operate as a profit-driven, transparent entity. However, some four years on, it has merely perfected the art of unaccountability under a new name.

The figures tell a damning story. Despite being Africa’s largest oil producer, Nigeria has consistently struggled to meet its OPEC production quota. Meanwhile, crude oil theft has become so institutionalised that some estimates suggest over 400,000 barrels are lost daily. These thefts cannot happen without the complicity—or, at least, the negligence—of insiders. But what has the NNPCL done? Issue denials, shift blame, and continue operating under a cloak of impunity.

Even the Auditor-General’s reports over the years reveal billions of dollars in unremitted revenue, questionable subsidy claims, and shady contracts. In 2023 alone, the House of Representatives alleged that the NNPCL failed to remit over ₦2 trillion in oil revenue. Yet, no heads roll. No board members resign. No prosecutions follow.

The company’s opacity is another sore point. Unlike its peers in other oil-producing countries, the NNPCL does not publish independently audited accounts regularly. It remains a labyrinth of shell companies, middlemen, and politically connected contractors. Its management structure is top-heavy and inefficient. For a so-called limited liability company, it is ironic how little accountability it shows to the Nigerian people who are its ultimate shareholders.

But the deeper tragedy lies in what this means for the average Nigerian. As our oil wealth disappears into offshore accounts and vanity projects, our refineries remain comatose. We import fuel at premium prices, drain public coffers through opaque subsidies, and then queue at petrol stations like a war-torn country. The NNPCL’s failure is not abstract—it is felt in every power outage, every inflated transport fare, every collapsed business.

What is more?

The ongoing revelations from the oil company are simply mind-boggling… sleaziest of stealings are continually being perpetrated…humongous amount of money, running into trillions of Naira and billions of Dollars are allegedly finding their ways into the pockets of few individuals who are far richer than the NNPCL, and even some of the federating units of the country.

While the National Assembly is still mouthing its will not to allow the stealings to be swept under the carpet, then came the clincher confirming the fear of Obasanjo that NNPCL is a dead horse- Bayo Ojulari, the man currently saddled with the responsibility of revamping the company, dropped the banger as he reportedly said it may be sold off.

In the midst of the mind-boggling sleaze and the near-comatose of the oil company, there were reports of high insensitivity on the part of the new hands at the helms of affairs who were attending meetings outside of the country, using private jets. Could this ostentatious living be coming from their pockets or largesse coming from the pervading decadence that the NNPCL represent?

It is time to ask a hard question: does the NNPCL serve Nigeria’s interests or just a few entrenched interests? If it cannot deliver transparency, accountability, and results, then perhaps it is time to break it up, open the sector fully to competitive private players, and let market forces—not political connections—drive efficiency.

Can the Nigerian national legislative exercise the will and unearth the terrible goings-on in the NNPCL? Without doubt, the late President Yar’ Adua will be turning in his grave, full of regrets that he upturned the decision of his benefactor, President Obasanjo, and bought back the company.

One thing remains clear in all of this national tragedy represented by the NNPCL- Nigeria and Nigerians deserve better than this bloated behemoth that feeds fat on our collective misery. It is not too late to heed warning by Obasanjo. But we must do more than listen—we must act.

The President Tinubu administration has an opportunity to make a clean break, but only if it is willing to do what past governments have avoided: initiate a forensic audit of the NNPCL, prosecute those found wanting—no matter how powerful—and overhaul the company’s structure from the ground up. Anything less is just cosmetics on a corpse.