The rise in anti-immigrant sentiment once again in mostly low-income South African communities, also known as townships, has left immigrants and refugees fearing for their safety.

South African security forces have increased their numbers in some of these areas, according to police minister Bheki Cele, who arrived in Diepsloot, a working-class township in the north of Johannesburg, following violent protests against undocumented foreigners that left one Zimbabwean man dead on Wednesday.

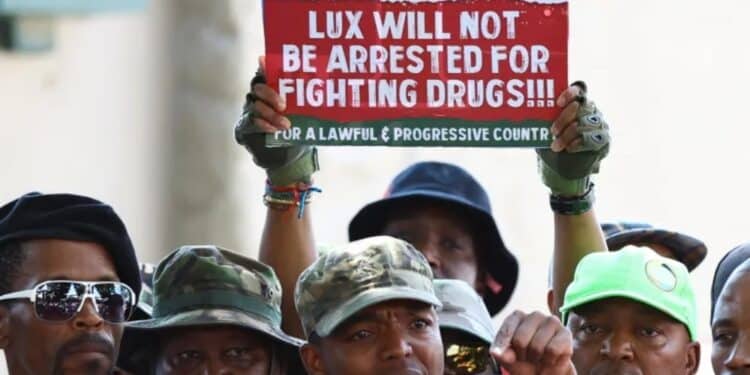

At the root of the tensions is a renewed campaign against “illegal immigrants,” spearheaded by an unregistered community organisation called Operation Dudula.

Who are they?

Operation Dudula is a splinter group from a faction in the Put South Africans First movement, an organisation that first popularised and renewed anti-immigrant campaigns on social media before finding expression on the ground.

The new movement is led by 36-year-old Nhlanhla ‘Lux’ Dlamini, born Nhlanhla Paballo Mohlauli.

Labelled by some as “xenophobic and dangerous,” it was founded in Soweto a few months after the July 2021 riots that erupted when former president Jacob Zuma was sentenced to jail for contempt of court.

Dlamini’s popularity skyrocketed when he led hundreds of his followers through a march in Soweto on June 16, 2021—the 45th anniversary of the Soweto Uprising.

They targeted suspected drug traffickers and businesses that allegedly hired illegal foreigners to pay them lower wages than legally required.

Once a historic Black township at the forefront of anti-apartheid resistance and the home of iconic duo Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu, Soweto is now the epicentre of tense clashes between residents and other African nationals.

Following the launch of Operation Dudula, several anti-immigrant groups started emerging in working-class communities across the Gauteng and Kwa-Zulu Natal provinces, going by the same name or variations of it, such as the Alexandra Dudula Movement.

Dudula translates to “force out” or “knock down” in the Zulu language, and expresses the common purpose of organisations like it: to force out African immigrants.

According to Operation Dudula, its campaign is driven by the burden placed on public health services, job opportunities and social grants due to an “influx of illegal immigrants.”

How did we get here?

South Africa is one of the most unequal countries in the world, according to a recent World Bank report titled ‘Inequality in Southern Africa’. The report highlighted how inequality is consistent with racial disparities as “10 per cent of the population owns more than 80 per cent of the wealth.”

An estimated 10 million people in South Africa live below the food poverty line, while the unemployment rate is at a record high of almost 40 per cent amongst Black South Africans, according to Statistics South Africa.

Poverty, unemployment, and crime are the greatest sources of contention, as Operation Dudula and its members believe that illegal foreigners – and sometimes “foreigners” in general, depending on who you ask – are the reason that South Africa’s public socioeconomic systems do not benefit its native Black majority.

Last month, the home affairs minister, Aaron Motsoaledi, said an estimated 3.95 million foreigners live in South Africa and admitted that the government did not have records accounting for undocumented immigrants.

On Tuesday, President Cyril Ramaphosa officially condemned the group following weeks of public pressure from civil society organisations amid fears of another escalation of xenophobic violence. He described it as a “vigilante-type” that needs “to be stopped.”

Over the years, South Africa has seen a spate of xenophobic clashes between locals and foreigners. The worst episode took place in 2015 and resulted in several foreign nationals closing their businesses and requesting voluntary repatriation to their home countries.

But Operation Dudula, the latest leader of the purge, denies that it is a vigilante group driven by xenophobia or specifically focused on African nationals. Instead, the members claim that they are “cleaning up communities” and “providing opportunities” to South Africans marginalised by the national government.