Nigeria’s tourism sector is weeping — not because it lacks beauty, not because it lacks assets, not because it lacks global appeal — but because it lacks sustained political will, institutional protection, and policy continuity. It is a sector that should be roaring like a lion in Africa’s economic savannah, yet it limps like an orphan denied inheritance.

Tourism is not a decorative appendage to the economy; it is a vast economic network a living ecosystem that binds aviation, hospitality, culture, transportation, agriculture, entertainment, trade, security, environment, and digital services into one powerful value chain. When tourism breathes, multiple sectors breathe. When it stagnates, allied industries suffocate.

Across the world, nations are tapping into this golden network with deliberate precision. Countries that do not possess half of Nigeria’s natural and cultural endowments are smiling to the banks through tourism receipts, destination branding, and heritage diplomacy. Even Ghana our neighbour has leveraged focused policy direction, diaspora engagement, and heritage tourism to command global attention. Yet Nigeria, richly endowed from Port Harcourt to Kaura Namoda, from Lagos to Maiduguri, continues to crawl where it should be sprinting.

We have over 789 kilometres of coastline and beach lines, more than 48 waterfalls cascading through breathtaking landscapes, over 15 National Parks, and more than 48 pristine forest reserves.

We possess heritage corridors, sacred groves, cultural festivals, warm springs, game reserves, ancient cities, mountain plateaus, and biodiversity sanctuaries that many nations can only dream of.

From Ikogosi Warm Springs to Arinta Waterfalls, from Zuma Rock to Yankari Games Reserve, from the blue waters of Ozmini to the temperate majesty of Obudu Mountain Resort, Nigeria is a tourism continent disguised as a country — yet we are not making headway.

Attempts have been made in the past, particularly under the two eras of Chief Olusegun Obasanjo, both as Military Head of State and later as Civilian President. Those periods witnessed structured tourism conversations, institutional awakenings, and modest global positioning. But after those eras, a relapsing fever gripped the sector. Progress would emerge and vanish. Frameworks would be drafted and abandoned. Institutions would be created and weakened.

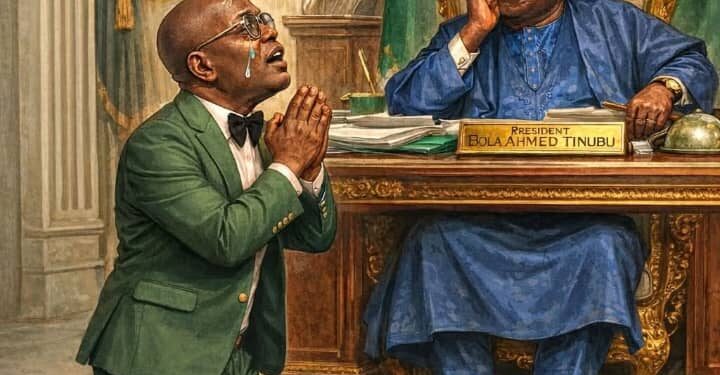

A spark was again fired under you Sir, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu when you created a standalone Federal Ministry of Tourism was established in August 2023 — a historic elevation that placed tourism on the political front burner as a vehicleor economic diversification.

Then stakeholders celebrated because, for the first time in decades, tourism had a cabinet voice unburdened by cultural and information overshadowing.

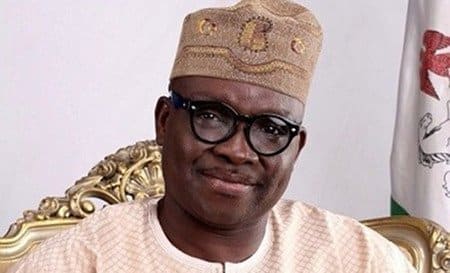

Nigeria’s tourism sector under Lola Ade-John

Under the leadership of Mrs. Lola Ade-John, that Ministry pursued foundational reforms despite operating in an almost hostile administrative climate. She inherited a ministry without a dedicated office, without a Permanent Secretary, and without seed funding — a ministry forced to finance activities out-of-pocket.

Yet governance restructuring began. The long-stagnant National Tourism Policy of 2005 was set on the path of review in collaboration with the Nigerian Economic Summit Group.

Efforts commenced to revive the Presidential Council on Tourism — a critical inter-ministerial platform needed to synchronise aviation, infrastructure, security, environment, and investment frameworks. Nigeria’s return to the World Travel Market London after a decade-long absence was championed, signalling diplomatic and commercial re-entry into the global tourism marketplace.

Despite health setbacks that interrupted her tenure for months, the sector felt a pulse again. Stakeholders re-engaged. Hope resurfaced. Tourism, for a brief moment, heaved a sigh of institutional rebirth.

Then came October 23, 2024 — the abrupt dissolution of the standalone Ministry and its merger into the Federal Ministry of Arts, Culture, Tourism and Creative Economy. Tourism, once elevated to cabinet priority, was structurally demoted to a departmental function. The justification was cost-cutting; the consequence was policy regression.

The old problem returned subordination, dilution, and bureaucratic overshadowing. The impact was immediate and measurable. At the World Travel Market London 2024

the very platform the Ministry had fought to re-enter Nigeria’s federal executive presence was conspicuously absent. No coordinated national branding, no high-level delegation, no strong federal visibility. Participation was salvaged largely by sub-national actors and private associations, sending troubling signals to global investors about Nigeria’s seriousness and policy consistency.

What this institutional reversal exposed is a painful policy paradox: Nigeria recognises tourism’s vast potential but fails to sustain the governance architecture required to actualise it.

Tourism stagnation is not accidental; it is engineered through structural fragility, financial starvation, and immediate policy reversals. Merged ministries dilute focus. Implementation culture remains weak. Global branding becomes inconsistent. Cross-sectoral coordination collapses. A sector that requires aviation alignment, security assurance, transport infrastructure, environmental protection, and diplomatic marketing cannot thrive without ring-fenced executive authority. Tourism is not leisure alone — it is employment, foreign exchange, SME stimulation, infrastructure justification, cultural diplomacy, and national image projection rolled into one economic engine.

Mr. President, the sector is not asking for decoration; it is asking for structure. The brief life of the standalone Ministry proved one undeniable truth: when tourism has an independent voice at the Federal Executive Council, it breathes. When it is merged and muted, it suffocates.

Within that short window, the sector heaved a sigh of development under Lola Ade-John despite structural handicaps. Imagine what could happen with full funding, institutional stability, and sustained executive backing. Nigeria’s tourism sector is weeping — but it is not broken. It is waiting… waiting for ring-fenced governance, waiting for policy protection, waiting for executive courage.

Mr. President, history beckons. Kindly reconsider the restoration of a Standalone Federal Ministry of Tourism. Let tourism breathe. Let it grow. Let it diversify our economy. Let it employ our youth. Let it project Nigeria’s image globally. Nations that ignore tourism today will import prosperity tomorrow — and Nigeria has far too much beauty to remain poor from it.

*Barrister Ojo-Lanre, Esq. is a tourism advocate