President Donald Trump’s executive order to end birthright citizenship in the US has sparked several legal challenges and some anxiety among immigrant families.

For nearly 160 years, the 14th Amendment of the US Constitution has established the principle that anyone born in the country is a US citizen.

But as part of his crackdown on migrant numbers, Trump is seeking to deny citizenship to children of migrants who are either in the country illegally or on temporary visas.

The move appears to have public backing. A poll by Emerson College suggests many more Americans back Trump than oppose him on this.

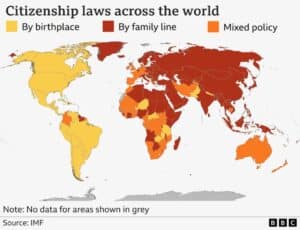

But how does this compare to citizenship laws around the world?

Birthright citizenship worldwide

Birthright citizenship, or jus soli (right of the soil), is not the norm globally.

The US is one of about thirty countries, mainly in the Americas, that grant automatic citizenship to anyone born within its borders.

In contrast, many countries in Asia, Europe, and parts of Africa adhere to the jus sanguinis (right of blood) principle, in which children inherit their nationality from their parents regardless of their birthplace.

Other countries have a combination of both principles, also granting citizenship to children of permanent residents.

John Skrentny, a sociology professor at the University of California, San Diego, believes that, though birthright citizenship or jus soli is common throughout the Americas, “each nation-state had its own unique road to it”.

“For example, some involved slaves and former slaves, some did not. History is complicated,” he says. In the US, the 14th Amendment was adopted to address the legal status of freed slaves.

However, Mr Skrentny argues that what almost all had in common was “building a nation-state from a former colony”.

“They had to be strategic about whom to include and whom to exclude, and how to make the nation-state governable,” he explains. “For many, birthright citizenship, based on being born in the territory, made for their state-building goals.

“For some, it encouraged immigration from Europe; for others, it ensured that indigenous populations and former slaves, and their children, would be included as full members and not left stateless. It was a particular strategy for a particular time, and that time may have passed.”

Shifting policies and growing restrictions

In recent years, several countries have revised their citizenship laws, tightening or revoking birthright citizenship due to concerns over immigration, national identity, and so-called “birth tourism” where people visit a country to give birth.

India, for example, once granted automatic citizenship to anyone born on its soil. But over time, concerns over illegal immigration, particularly from Bangladesh, led to restrictions.

Since December 2004, a child born in India is only a citizen if both parents are Indian or if one parent is a citizen and the other is not considered an illegal migrant.

Many African nations, historically following jus soli under colonial-era legal systems, later abandoned it after gaining independence. Today, most require at least one parent to be a citizen or a permanent resident.

Citizenship is even more restrictive in most Asian countries, where it is primarily determined by descent, as seen in nations such as China, Malaysia, and Singapore.

Europe has also seen significant changes. Ireland was the last country in the region to allow unrestricted jus soli.

It abolished the policy after a June 2004 poll, when 79% of voters approved a constitutional amendment requiring at least one parent to be a citizen, permanent resident, or legal temporary resident.

The government said the change was needed because foreign women were travelling to Ireland to give birth to get an EU passport for their babies.

One of the most severe changes occurred in the Dominican Republic, where, in 2010, a constitutional amendment redefined citizenship to exclude children of undocumented migrants.

A 2013 Supreme Court ruling made this retroactive to 1929, stripping tens of thousands – mostly of Haitian descent – of their Dominican nationality. Rights groups warned that this could leave many stateless, as they did not have Haitian papers either.

International humanitarian organisations and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights widely condemned the move.

As a result of the public outcry, the Dominican Republic passed a law in 2014 that established a system to grant citizenship to Dominican-born children of immigrants, particularly favouring those of Haitian descent.

Mr Skrentny sees the changes as part of a broader global trend. “We are now in an era of mass migration and easy transportation, even across oceans. Now, individuals also can be strategic about citizenship. That’s why we are seeing this debate in the US now.”

Legal challenges

Within hours of President Trump’s order, Democratic-run states, cities, civil rights groups, and individuals launched various lawsuits.

Two federal judges have sided with plaintiffs, most recently District Judge Deborah Boardman in Maryland on Wednesday.

She sided with five pregnant women who argued that denying their children citizenship violated the US Constitution.

Most legal scholars agree President Trump cannot end birthright citizenship with an executive order.

Ultimately, the courts will decide this, said Saikrishna Prakash, a constitutional expert and University of Virginia Law School professor. “This is not something he can decide on his own.”

The order is now on hold as the case passes through the courts.

It is unclear how the Supreme Court, where conservative justices form a supermajority, would interpret the 14th Amendment if it came to it.

Trump’s justice department has argued it only applies to permanent residents. Diplomats, for example, are exempt.

But others counter that other US laws apply to undocumented migrants, so the 14th Amendment should, too.