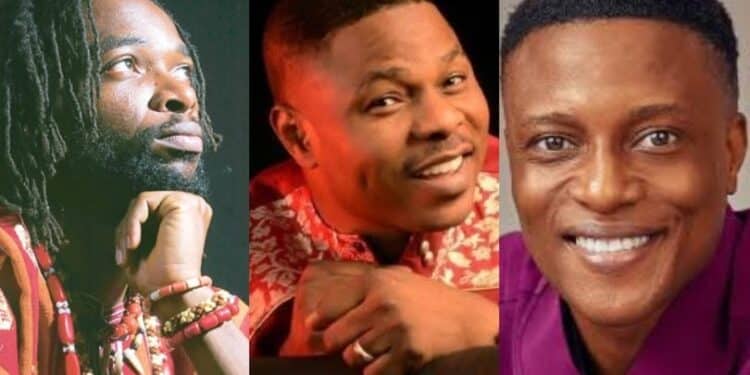

The Nigerian music industry is facing a renewed debate over creative integrity and intellectual property (IP) rights following serious allegations leveled by legendary folk singer Segun Akinlolu, popularly known as Beautiful Nubia. In a statement released Thursday, February 19, 2026, via X, the veteran musician accused gospel singer, Yinka Ayefele and rising gospel artist BBO of unauthorised use of his 2002 classic, “Seven Lifes.” The dispute centers on Ayefele’s 2012 track “My Faith in God (Igbagbo Ireti)” and BBO’s 2026 release “Amin,” both of which Beautiful Nubia claimed appropriated core melodies from his original work. “There was Yinka Ayefele with ‘My Faith in God (Igbagbo Ireti)’ in 2012 and now someone called BBO with ‘Amin’ this year. Both stole their melodies from our original song ‘Seven Lifes’,” Akinlolu wrote. “When will Nigerians (especially the so-called gospel musicians) learn to respect copyright?,” Beautiful Nubia added. As of press time, neither Ayefele nor BBO has issued an official rebuttal.

A Pattern of “Creative Borrowing”

The allegations against Yinka Ayefele highlight a long-standing friction between traditional “jingle-style” composition and modern copyright law. Ayefele, whose roots trace back to radio production, has built a career on high-energy medleys that frequently incorporate existing tunes. Meanwhile, this approach often crosses the line from “inspiration” to “infringement.” It is noteworthy that Ayefele’s early career, both as a jingle producer and a gospel singer leaned heavily on tweaking melodies<span;> of existing works rather than original composition. For instance, his debut album, aside from where he sing-praised his supporters, leaned on the melodies of Olando Owoh; then hymns. Interestingly, Yinka Ayelefe on his Opeyemi on Fresh FM, while interviewing Tunde Onijoba (Emi Awon Wooli), recently, stated that when he was informed about some singers using his songs, he told them “singers will continue to sings some songs until they get to where theyre supposed to get to.” Then, he jokingly told Tunde Onijoba that he may likely use his popular Emi Awon Wooli. This remarks is an inkling to views about freely using of existing melodies. Conversely, the industry has seen rare examples of transparency. Folake Umosen, for instance, explicitly stated in the video of her popular “Ko S’oba Bi Re,” that she was not the original writer but had recorded the version out of a personal spiritual connection to the melody.

The Global Context: Cover vs. Theft

While Beautiful Nubia’s frustration is palpable, the global music industry has a rich history of artists performing songs written by others. However, the distinction lies in licensing and attribution. Instances include: Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You,” written and originally performed by Dolly Parton; Aretha Franklin’s “Respect,” written and originally performed by Otis Redding; Jimi Hendrix’s “All Along the Watchtower,” Written by Bob Dylan, and Elvis Presley’s “Hound Dog,” originally recorded by Big Mama Thornton, among many others. Even locally, Legendary juju singers, King Sunny Ade and Ebenezer Obey-Fabiyi, used existing melodies. “Aye Yi ki Se’le Mi mi,” by Ebenezer Obey-Fabiyi was originally written and recorded by Jim Reeves. Obey simply translated the song to Yoruba, and produced. Who knows whether he sought Jim Reeves’ manager or children’s permission since Jim Reeves had died before Obey produced the song. The difference between these iconic covers and the current “brouhaha” in Nigeria is the legal framework. Western icons generally secure mechanical licenses or sampling clearances, ensuring the original creators are compensated. In the Nigerian gospel scene, there appears to be a persistent myth that “spiritual” content is exempt from secular law.

The Legal Reality: Beyond “Giving Credit”

For artists like BBO, who utilised the intro and chorus melody of “Seven Lifes” for his track “Amin,” the legal exposure is significant. Under Nigerian copyright law, “interpolation”—re-singing a melody without using the original audio—still requires explicit permission from the songwriter or publisher. It is of note that the following common defenses hold no weight in court:

- “I gave credit”: Credit is a courtesy; it is not a legal substitute for permission.

- It’s for the church”: Religious intent does not grant a license to bypass IP laws.

- “I only used a small part”: Even a five-second signature melody (like an intro) is protected.

- “I didn’t know”: Ignorance is not a defense under the law.

The Way Forward

The Beautiful Nubia dispute may serve as a much-needed “litmus test” for the industry. If the veteran singer pursues legal action, it could force a shift toward professionalization, encouraging “voice-only” artists to hire professional songwriters and tune composers rather than relying on unauthorized adaptations. By enforcing these boundaries, the industry may finally see the emergence of a robust market for professional songsmiths, ensuring that those who possess the “gift of the voice” and those with the “gift of the pen” can collaborate legally and profitably.